NINA SILVEBERG - HOMESICK

works

The Bare Line

by Maria Vittoria Pinotti

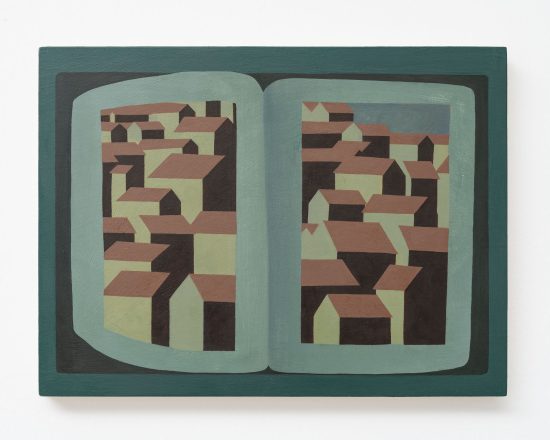

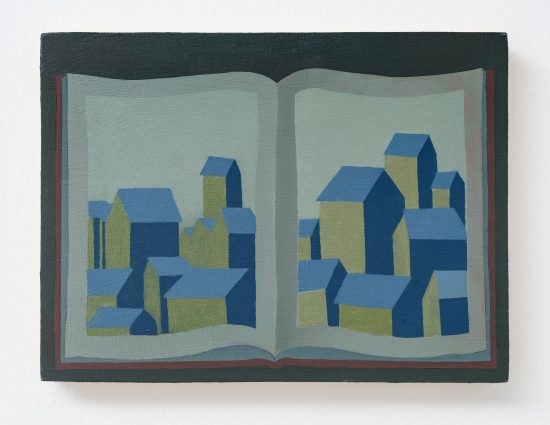

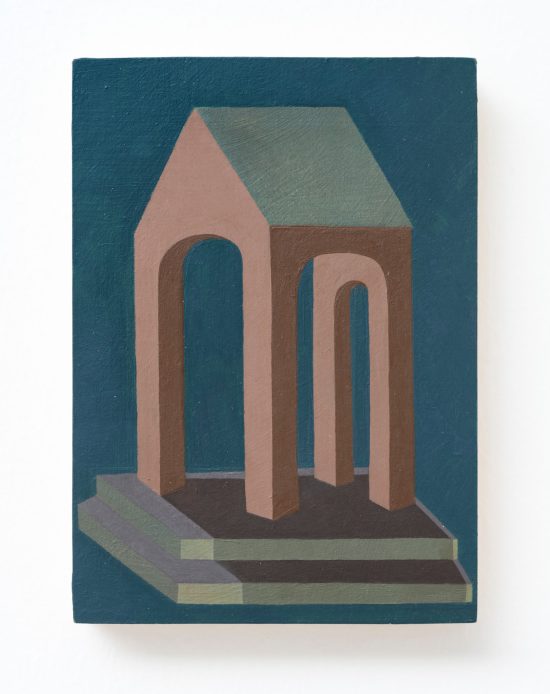

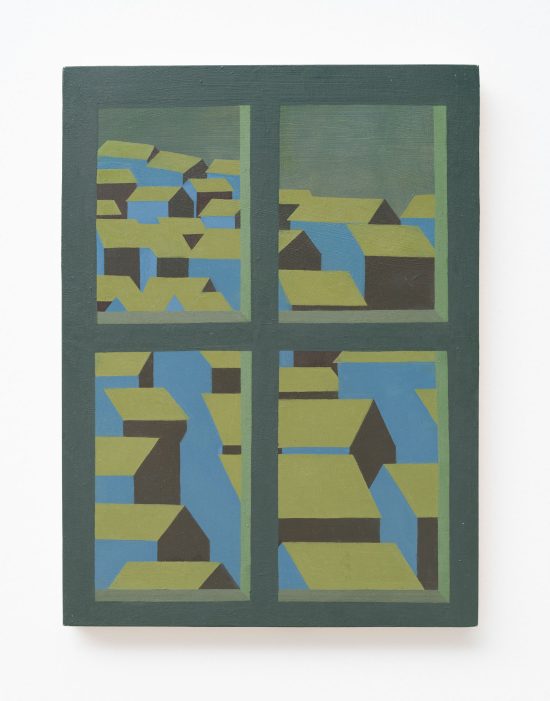

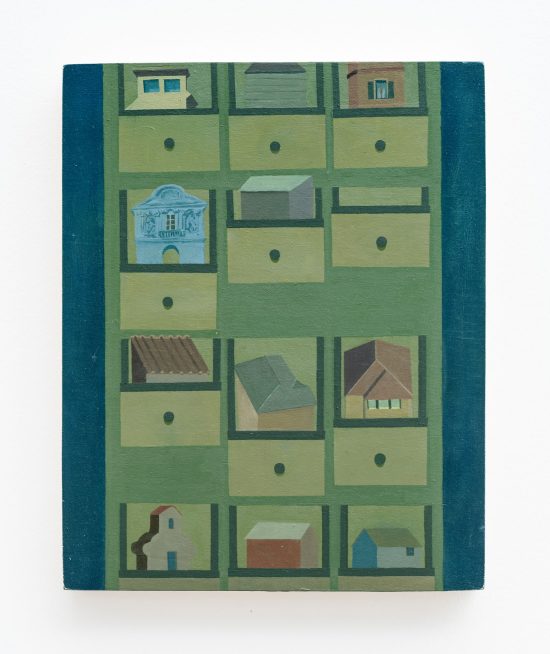

There is a hidden line running through all of Nina Silverberg’s works. It moves slowly, stretching out thinly across paintings no larger than an open handkerchief; it crosses architectures, brushes the pages of books, opens windows and half-opens drawers. Even if veiled, its development can certainly be imagined – it has a sharp and never uncertain profile, working to define the geometries of only a few selectedsubjects. So, although the trajectory of the line is quite predictable, it does not replicate or indiscriminately neutralize what it passes through. Instead, it works to unite perspectives of the same element, revealing how the act of repetition becomes the ritual of an entire artistic inquiry. Yet it seems Silverberg’;s true focus is to capture absence. The pages of the books are devoid of writing, everything in the architecture remains still, the windows – alternately shut, ajar, or wide open – escape all scenic views, transforming domestic tranquility into a metaphysical threshold where only silence exists. What has happened, and what is about to happen? How much life has passed through these spaces, and how much more will pass through? Perhaps none, because in this total formal simplicity, there is no trace of psychology, no presence – only an abyssal distance from human matters, revealing a form of painting that feeds on the cult of absence.

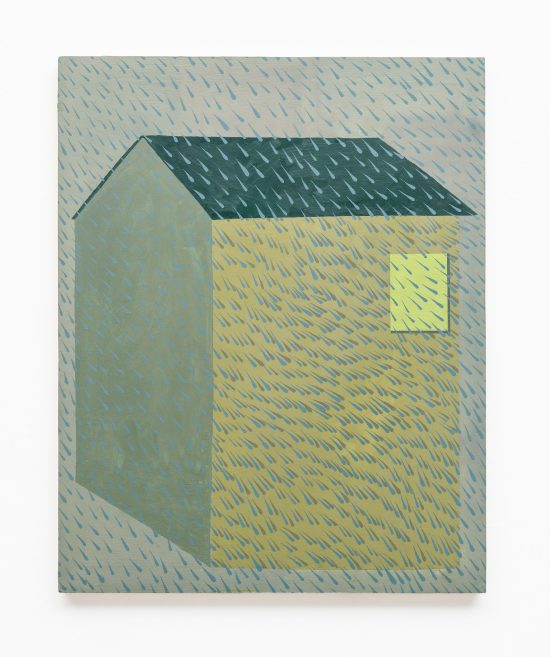

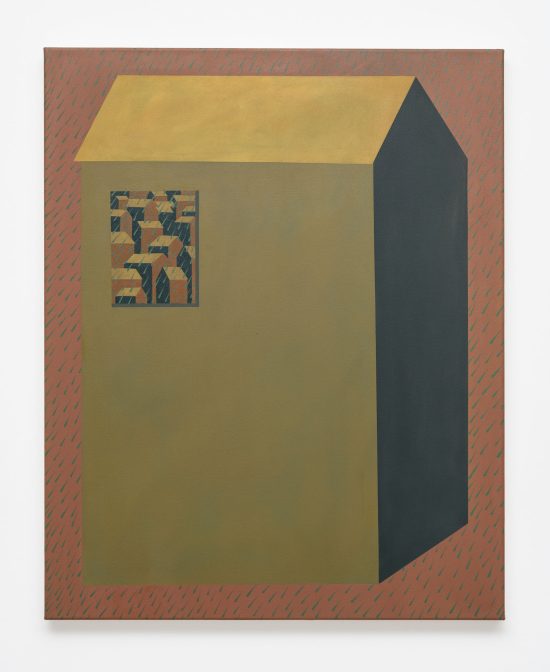

Silverberg’s canvases are extremely simple and spontaneously naive. In this painting reduced to the essential and devoid of artifice, the tones are modulated through a few earthy juxtapositions, laid out in precise fields, almost as if applied by a flat stamping tool focused on tone. The space is geological, meaning it explores the development of forms over time, ultimately creating a stable tension between stillness and their potential transformation. For the painter, the history of images has solidified, and this orderly essentiality governs stone-like scenarios where houses are frozen in the hardness of their matter, and raindrops fall on their roofs like the tips of sharp spears.

In this absurd sensibleness, things become truer than truth itself, because their most primitive and radical aspect is revealed – as if every view were being seen for the first time. Each scene holds a strange truth that is neither natural nor real, for in this formal nakedness lies the origin of everything, bringing us closer to its bare bones. This condition, which extends beyond spatial boundaries, leads us to think that perhaps the time has come for painting to free itself from the effort of representation, and instead attain a natural simplicity through the most primitive and basic elements of Euclidean geometry. This is exactly what happens in Silverberg’s work: spatiality is the starting point of every piece, and the more anonymous the forms, the more firmly they are fixed in their spatial alteration. However, what emerges is a timid kind of painting, one that allows itself to be discovered slowly, only through certain clues. It seems that each image reveals itself like the petals of a flower beginning to bloom – always ready to close up again quickly, so as not to lose their freshness. It is an unusual approach, a form of audacity quite unlike much of today’s contemporary painting, aiming to achieve a jagged simplification of what is depicted, rather than its natural likeness. Amid all this, as the gaze moves across the works, the question resounds: “Is there something rather than nothing?” Probably yes, because in recognizing the absence of scenic artifice and the total indifference between foreground and background, what is represented is indeed a lived-in reality, yet one marked at the same time by a strong destructive tension – one that transformsmnothingness into something both welcoming and distant. What is most striking is how, by embracing the cult of absence and silence, the artist creates forms of anonymous simplicity, prompting us to imagine that the figures are born as self-taught silhouettes – figures whose birth the painter is called to witness, to accompany in their growth, until their endless transformation is fixed. As if we were uncovering the rules of a game, Silverberg works with forms, untangling them in space much like the mechanism of Chinese boxes: increasing in size, they fit one inside the other, without following a specific logical order except that of structures that must be resolved through various fitting attempts. Thus, when approaching each work, one has the impression that, among the infinite possibilities of these structures, space becomes a plastic element – a malleable material that ceases to be mere abstraction. In this way, as we analyze the paintings, the antinomies continue: likeness is achieved through unalike means, landscapes are treated in an archaic way and with a clearly illusory spatiality, maintaining an absence of scaled distances and a disrupted succession of planes in depth.The ancient urban spaces of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s schematic medieval cities and the soft plasticity of Simone Martini’s drapery return to our eyes. Like them, Silverberg does not illustrate the landscape but rather its concept – not an optical view, but a mental construction composed of

varying metric scales. Especially in these anonymous, meditative territories – devoid of topographical elements – form passes from darkness to light, and in this perpetual alternation, the hidden line running through all the works alternately relaxes and stretches toward virtual, metaphysical destinations.

It is the line of bare life: dynamic, pure, even as it travels slowly through the forms, cutting them sharply with precision. At times, it traces their sinuous curves, transforming mechanical relationships into pure configurations. This is a linear painting, charged with a specific solid weight, stripped of all ornament and reduced to a trace.

Installation view

PRESS

Art(a)part of Culture:

Juliet art Magazine:

Nina Silverberg: la nuda linea

Artuu:

La città immobile: Nina Silverberg e la geografia emotiva di Roma